I’ve been trying to work out to describe how our daughter Emily is related to the various people she’s been meeting over the last several weeks. To my Mum and Dad’s siblings, she’s a great-niece. To my cousins, she’s a first-cousin once removed. To my cousin’s children, she’s a second cousin.

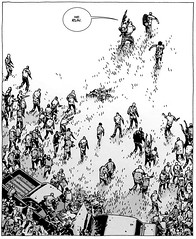

This is all right and true, as established by the common European kinship relationship system, drawn out here.

A few people commented that “[East] Indians have a different way of doing it,†and indeed they do. As to various native American tribes, the Chinese, the Scandinavians and everyone else. As Emily has claim to several of these traditions, I thought I’d look into it to see if there was anything in the Dravidian kinship system (on my Father’s side) or Indo-Aryan (on my Mother’s) or Danish (on Amanda’s mother’s) side to bear this out.

Turns out, not so much. The Danish tradition looks pretty similar to the standard European one as far as I can tell, although there is gender-attribution in the kinship terminology – you reference whether the relationship is on your father or mother’s side.

Similar things hold true as far as using gender to reference relationships in the various Indian traditions, but truth be told, it gets mind-bendingly confusing and no-one in my family uses these terms to mean what they mean in common English usage. From Wikipedia:

The Dravidian kinship system involves selective "cousinhood." One’s father’s brother’s children and one’s mother’s sister’s children are NOT cousins but brothers and sisters "one step removed." They are considered "consanguinous" ("pangali") and marriage with them is strictly forbidden as it is "incestuous." However, one’s father’s sister’s children and one’s mother’s brother’s children are considered cousins and potential mates ("muraicherugu"). Marriages between such cousins are allowed and encouraged. There is a clear distinction between "cross" cousins who are one’s true cousins and parallel cousins who are in fact "siblings". Like Iroquois people, Dravidians refer to their father’s sister as "mother-in-law" and their mother’s brother as "father-in-law."

As Amazing as Amanda is, I think she’d struggle with the idea that I had 8 mother-in-laws when we got married, and indeed I find the idea that half my first cousins were “potential mates†based on random gender bias more than a bit bizarre. There’s even more explanation of this perspective here. Given that I know how genetics work, I’m going to dismiss this kinship terminology as inappropriate for our purposes, especially given no-one I’m related to uses these relationships to have these meanings or consequences.

On the Aryan side, I’ve struggled to find freely available web resources explaining how the various North Indian groupings view kinship. Similarly to the Danes, there are gender specific biases (my mother is technically Emily’s “Dadi†– ‘Father’s mother’, although she doesn’t like the term so we arbitrarily use something else). Most people of my generation, rather than reference their “mother’s sister’s son or daughter†just use the word “kÓ™zin†to cover all of these (in the Sindhi tradition, according to this – section 3.2.1). Which makes it seem vaguely similar to the European tradition.

So that’s it. There’s no “grand auntsâ€, second cousins are what the children of first cousins are to each other and first cousins aren’t “uncles†to each others’ cousins’ children, but first cousins once removed. I’m sticking with that until I read anything obviously and heroically contradictory :-)

Of course, it’s been abundantly clear that this issue is anything but simple and a number of academic papers have been authored on the subject, including some by none other than my own professor mother. But what is clear to me is that the desire to attribute “aunt†or “uncle†ship to everyone is little to do with kinship – rather it is steeped in the culture of respect for elders and the titles are used for that purpose alone. Which, for me, is no bad thing.

I’ve never been particularly interested in art. When I was a kid, visiting the UK with my family, I remember near-terminally long visits to the National Gallery – the principle purpose of which always seemed to be to buy prints from the Great Masters (Van Gogh, Constable etc) for our house in Malaysia. I was always hopeless at actually creating anything, which I think served to dim my interest and aspirations in that direction, despite Mr Kwan and Miss Genting’s best efforts at our art classes – at home and at school.

I’ve never been particularly interested in art. When I was a kid, visiting the UK with my family, I remember near-terminally long visits to the National Gallery – the principle purpose of which always seemed to be to buy prints from the Great Masters (Van Gogh, Constable etc) for our house in Malaysia. I was always hopeless at actually creating anything, which I think served to dim my interest and aspirations in that direction, despite Mr Kwan and Miss Genting’s best efforts at our art classes – at home and at school.